Stories

The Shadow of Robert Gray

by Brian D. Ratty

©2022

What a crying shame when a person’s final days are marked with poverty and thoughts of lost prospects. So it was with Yankee trader Captain Robert Gray. He died at sea at the age fifty-one, near Charleston, South Carolina in 1806. He had reaped no rewards for his years of discovery, and thought himself a failure to the very end. But today Robert Gray’s deeds cast a long shadow across the rugged coastline of the Pacific Northwest.

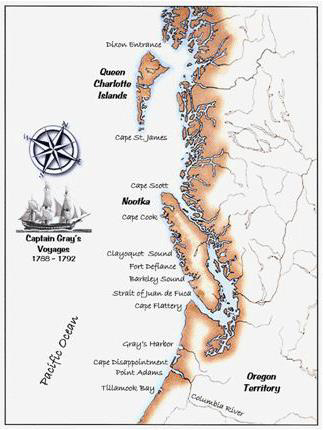

Long before Lewis & Clark trudged across the heartland, Captain Gray was exploring and charting the pristine lands and waterways of the North American Continent. His maiden voyage to the Pacific was a daring enterprise that started in Boston Harbor in October of 1787 and ended in that same harbor on August 1790. During this passage, Captain Gray and his crew of the sloop Lady Washington were the first Americans to set foot on the Pacific West Coast when, in August of 1788, they discovered and named Tillamook Bay and the natives who thrived on its shore. Here they traded trinkets with the Indians for sea otter pelts. This they did for many months along the Pacific coastline

Gray and the crew from the Lady Washington meet the Tillamook Indians in August 1788

In 1789, now in command of the full-rigged ship Columbia Rediviva, he departed Nootka (Vancouver Island) with 1300 prime pelts and sailed for China, via the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) to trade the skins for Canton tea. When he arrived back in Boston, this black-eye-patched captain became the first American to have circumnavigated the globe. For this accomplishment, he was paraded through Boston and attended a reception held in his honor by Governor John Hancock. While the commercial value of this first voyage was disappointing, due to damaged tea from sea seepage, Captain Gray and the Columbia would depart for a second historic voyage to the Northwest in just six short weeks.

With the Columbia overhauled and made ready for sea again, he sailed from Boston Harbor in September 1790. After another long and treacherous trip around Cape Horn, Gray arrived at Clayoquot, an American trading post on Nootka in June of 1791. Here he met up again with the quirky Captain Kendrick and Gray’s old ship, the Lady Washington, which had been converted from a sloop (single mast) to a brigantine (double mast).

Replica of the brigantine Lady Washington

The two ships did not fare well during that summer of discovery. The Columbia sailed far north, trading with the natives, but some of his men were murdered by hostile Indians. The Lady Washington sailed for the Queen Charlotte Island and was also attacked when a few sailors went ashore. One among those slain was Captain Kendrick’s own son

The two ships returned to the Clayoquot in September, and the Lady Washington, under the command of Kendrick, set out for China with the furs from both ships. With winter approaching, Gray and his crew went to work, erecting a log fort which they named Defiance, and building a small 45-ton sloop that he christened Adventure. This ship was put under the command of Haswell, Gray’s second officer.

The Indians around the tiny American outpost were not friendly, so Gray and his men were obliged to keep constant vigil during the long, dark and wet winter. In early April, both vessels finally departed Clayoquot, with the Adventure sailing north for trade and the Columbia sailing for the rich sea-otter waters south of Nootka. But Captain Gray was not only searching for furs; he also explored many rivers, bays and inlets that he charted and named

A few weeks later, after arriving at the southern reaches of the Oregon coast, he turned north again, still seeking safe shelter for his ship and crew. Near the end of April, Gray sighted another ship and hove to for an exchange of greetings with Captain George Vancouver, a British Naval officer commanding the ship Discovery. Using a voice-horn, Gray informed the captain that he had recently lain off for nine days at the mouth of a large river where the tides were so violent that he dared not attempt to cross the bar. Vancouver doubted this news but noted in his journal: “If any river should be found, it must be a very intricate one and inaccessible to vessels of our burden.” The Discovery pushed on northward.

Gray continued on his journey, trading along the way. As he sailed up the coastline, the lookouts kept a keen eye out for any safe harbor in which the Columbia could lay over. On May 7th, Gray noted in his log book the discovery of what would become known as Gray’s Harbor: “Being within six miles of the land, saw an entrance in the same… We soon saw from our masthead a passage in between the sand-bars…as we drew in nearer between the bars, had from ten to thirteen fathoms, having a very strong tide of ebb to stem… in a safe harbor, well sheltered from sea by long sand-bars and spits.”

After spending but a short time in the harbor he had just discovered, Gray decided to sail south again to enter the mouth of the river he had sighted. This time luck and the tides were with him. A small yawl was launched to locate a safe passage across the treacherous bar which flowed with the strong, muddy current of a great river. According to the ship’s log, the crossing was made on May 11, 1792. Gray recorded the historic event: “At eight a.m. being a little to windward of the entrance of the harbor, bore away, and run in east-north-east between the breakers… When we were over the bar, we found this to be a large river of fresh water, up we steered… The north side of the river a half mile distant from the ship; the south side of the same two and a half miles distance… Vast numbers of natives came alongside… pumping the salt water out of our watercasks, in order to fill with fresh, while ship floated in. So ends.”

Gray had found the “Great River of the West” and yet described the event with one of history’s most understated comments: “So ends.” It is almost as if he considered this discovery unimportant. The Columbia sailed upriver, trading nails and other trinkets to the Indians for pelts, salmon, and animal meat. During this nine-day journey, Gray named many landmarks, bays and inlets. He also named the mighty river ‘Columbia,’ after his ship; the cape to the south bar became ‘Adams,’ and the one to the north, ‘Hancock’ (now referred to as Cape Disappointment). While on the river, Gray made a detailed chart of his discoveries, a copy of which was later acquired by Captain Vancouver.

Captain Gray sailed to China in 1793 and sold his furs. The venture must have not been profitable as he was not sent out to repeat it. Captain Kendrick of the Lady Washington was killed in the Sandwich Islands in a cannon accident in 1794. Gray’s many discoveries apparently impressed the public little more than they had impressed Gray himself, for he never sailed the far Pacific again. Neither recognition nor wealth befell him. Impoverished, he died in 1806 of yellow fever

Gray did not publish his discoveries concerning the Columbia River, nor those elsewhere along the far reaches of the Pacific coast. But Captain Vancouver did, giving Gray full credit for the many years he spent plying the waters of the Northwest. At the time, these discoveries by Gray were considered unimportant. However, other Americans soon followed up on the trading opportunities pioneered by Gray, who were called “Boston man” by the local Indians. By 1801, sixteen American vessels were engaged in the fur trade and the triangular route to China. Moreover, Gray’s discovery of the Columbia River was later used by the United States Government in support of its territorial claims to what Americans called the Oregon Country.

Today, Captain Gray’s shadow is more like a rainbow across the vast Pacific Northwest. Many namesakes for this famous explorer, Yankee trader and sea captain can be found on maps and nautical charts: harbors, bays, rivers, inlets and other geographic points are named for him. In addition, one Washington State county, a small village, a few avenues, and many schools bear his name. Captain Robert Gray may have died in obscurity, but his memory as a man with true grit and vision lives on

This article was condensed from the novel, Tillamook Passage, by Brian D. Ratty For more information on Oregon coastal Indians, the author recommends visiting the Tillamook Pioneer Museum, the Garibaldi Maritime Museum and/or the Clatsop County Historical Society.

Printable PDF file for The Shadow of Robert Gray